One of the many things I love about being an English teacher is the way we sit down as colleagues, typically late Spring, to discuss the books we’ll teach in the coming year. It’s fascinating to track both the national mainstays (The Crucible, Frankenstein, The Scarlet Letter) and those that are more regionally specific.

I’m happily in Cape Cod, so a salty nautical theme runs fast and furious. We have The Old Man and the Sea, so accessible and haunting, The Odyssey (duh) as well as new advocacy this year for Moby Dick (regionally relevant? Absolutely! Narratively? Challenging! Student engaging? We will see!)

I laughed with another English teacher this afternoon about the rightful endurance of Melville’s text, one everyone loves to say they have read, but no one ever seems to currently be reading.

More broadly, I am stunned by the publishing world, its enormous challenge, its infinitesimal chance. Just to publish anything with one of the major houses is an absolutely herculean achievement, worthy of taking lots of time off by the sea with all the lobster rolls and plenty of ice cream from Four Seas just to celebrate the jolly feat of having slipped through the barricades, making it to print. So few ever do!

Then there is the yet more infinitesimally slim, still greater herculean achievement of making it from the American bookshelf into the American classroom. Your work is being taught. Imagine. It is not lost on me that most of our texts were drafted by the long deceased, but of course we teach living writers all the time. One colleague is introducing Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H-Mart next year. A few years ago I brought Kevin Powers’ war novel The Yellow Birds into the New York public school system. These are all wins.

For as hard as it is to get published AND catch the attention of the teaching world—for your book to take flight in the classroom canon—I’m struck by the fickle hand of chance that is at play in all of this. As in, you’re just sitting in a meeting, the question gets asked generally (“Anyone want to introduce a new text next year?”), you briefly make your case, and boom! It’s in. Teachers rarely feel powerful, exactly, and this is indeed a moment to savor. Next thing you know, the list gets finalized, the order goes out, and you have cemented a new text into the order of business for the coming year. The whole thing goes down in less than ten minutes!

Yes, yes, we are ever mindful of how and why we make these bids. The book must be appropriate, in every sense of the word. It must be teachable. That is to say—given to assignments. To probing. To in-class examination and engaging classroom discussion. This is, of course, the work of the teacher, but some texts are undeniably better suited to being taught than, well, others. I’d love to teach Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland with all its melancholy evocation of a post-9/11 New York, but there’s just no way. The Great Gatsby (on which O’Neill has said he loosely based Netherland) remains a standard bearer in the American classroom to a large extent because 1) it is a very good length, 2) the characters are clearly sketched out and positioned well against each other, and 3) the themes are both relatable and aspirational. Lol, the green light and all that.

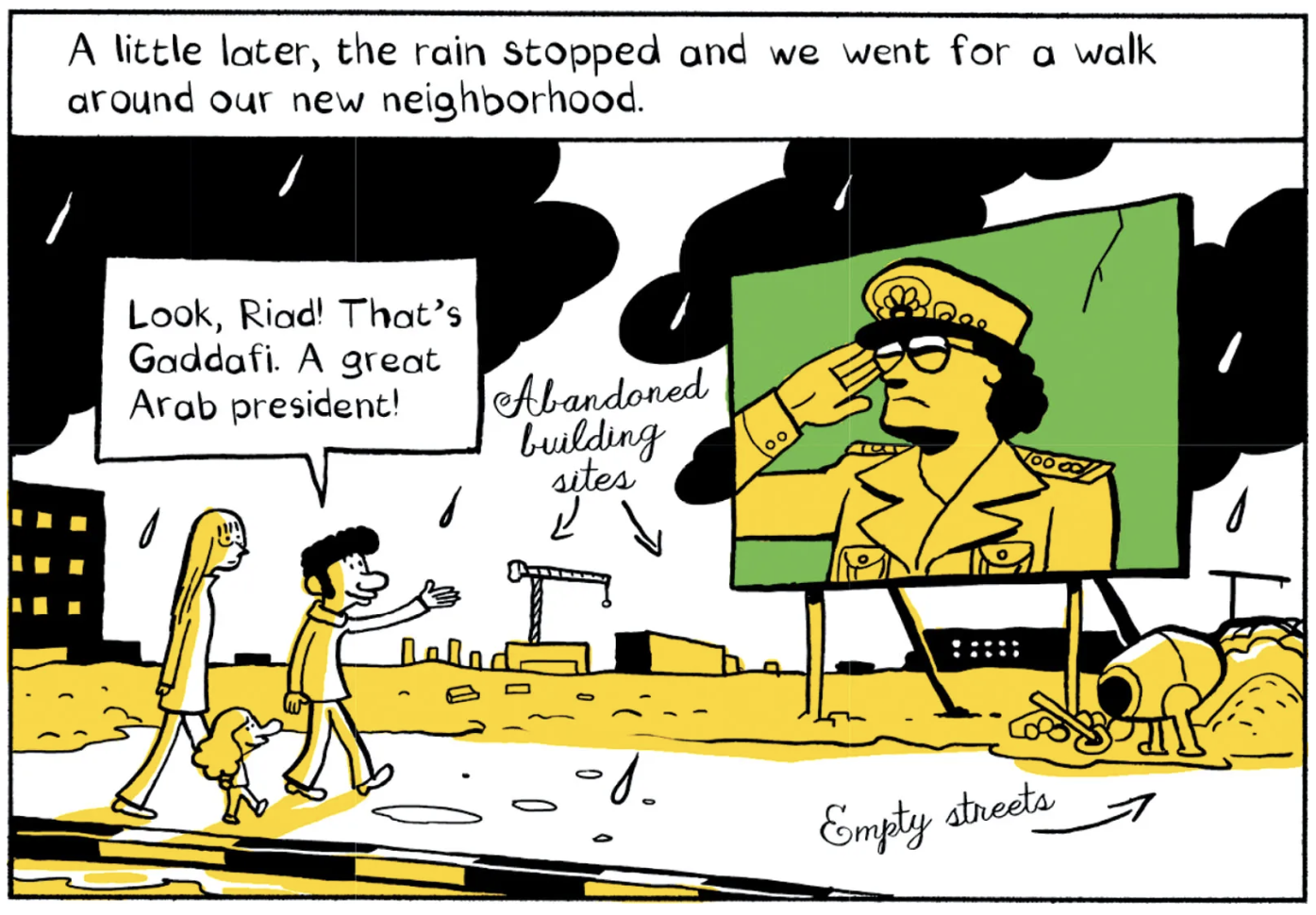

One text I advocated for this year, but sadly not for my own classes (might try to sneak it into my Grade 12 world lit course?) is Riad Sattouf’s The Arab of the Future. The first four volumes of this work are now out in English translation, and I’m dying to read the fifth. Translators of the world, stand up!

A graphic novel of a childhood in Libya and Syria, The Arab of the Future is full of the salt-sweat of elders, the curious textures of new meals, the frenzy of local educational practices in these two Middle Eastern countries.

Sattouf (in gamine profile here in the New Yorker and TAOTF reviewed here by the NYR) is half-French, and periodically returned to see his mother’s family in Lyon. So he maintains a one-foot-in, one-foot-out perspective on his Syrian father’s proclamation that he is, in fact, the Arab of the future. What he is, most immediately, is the observant child in between. His takes are by turns detailed, hilarious, macabre, frank, guarded, silly, serious and endlessly fresh.

I love every panel of The Arab of the Future and can’t wait to bring it to my sea-side students next year! Onward!